Explaining Acemoglu's model of directed technical change: a primer

Sat Apr 20 2019tags: academic economics macroeconomics explanation public draft

Table of contents

- Introduction and nontechnical explanation of the paradox

- We can solve the paradox by directed technical change

- But why would technical change be directed? Market effects

- Implications of the model, and comparisons to other models:

- Schumpeterian-Solow model

Introduction and nontechnical explanation

I first want to begin with a seeming paradox. Call this The Paradox. Consider these two facts:

- The number of highly-skilled workers has increased greatly over the past few decades.

- The skill premium[1] has increased despite a huge increase in high-skilled workers.

This seems counterintuitive. We know the labour market is determined by supply and demand. Therefore, it seems like the skill premium should decrease. We must conclude that something is making the skill premium go up despite the large influx of high-skilled workers.

What could it be? The answer is directed technical change: despite the fact that there are much more high-skilled workers nowadays, high-skilled workers have become much more productive than low-skilled ones, and therefore they command a higher wage.

But why have high-skilled workers become much more productive than low-skilled ones? Here's one possibility.

The nature of technological progress this few decades (e.g. computer, microchips) has been more suited for high-skilled workers.

At first glance, this explanation seems plausible. But if you think about it, it falls apart. See Acemoglu:

At the expense of oversimplifying, we can say that the microchip could have been used to develop advanced scanners that would increase the productivity of unskilled workers, or advanced computer-assisted machines that would be used by skilled workers to replace unskilled workers. (p.31)

In other words, technology itself does not confer disproportionate benefits on either group: what matters are the innovations that build upon that technological breakthrough.

The large increase in the number of high-skilled workers has made it more profitable for innovators to develop technologies that boost their productivity.

The real reason for directed technical change is actually a market size effect. Innovators focus their efforts on developing technologies that maximise their profit, and how much they can sell their R&D for depends on how many people use their technology. The more high-skilled workers there are, the more innovators develop for them, and the larger their productivity grows. This nicely turns the supply-and-demand story on its head, and gives us our answer to the paradox.

Here, I present Acemoglu's model of directed technical change, that formalises all we've just talked about. Why Acemoglu's model specifically?

- It is the only model in Oxford's macroeconomics course that talks about directed technical change/ high- vs low-skilled workers.

- It nicely explains The Paradox.

Review questions

What was the empirical motivation for Acemoglu's model of directed technological change?

How can the skill premium go up even as the relative supply of high-skilled workers goes up?

Formalising the paradox

The production function, as well as our utility function, is given by

There are high-skilled goods produced by high-skilled labour, and low-skilled goods produced by low-skill labour. We will ignore capital. Note here that this is a CRS production function.

We shall first disregard the technology growth function (how and change over time).

Because this is a competitive market, workers are paid their marginal productivities:

Combining these two equations we get the skill premium :

where is the elasticity of substitution[2]:

Taking logs on both sides gives

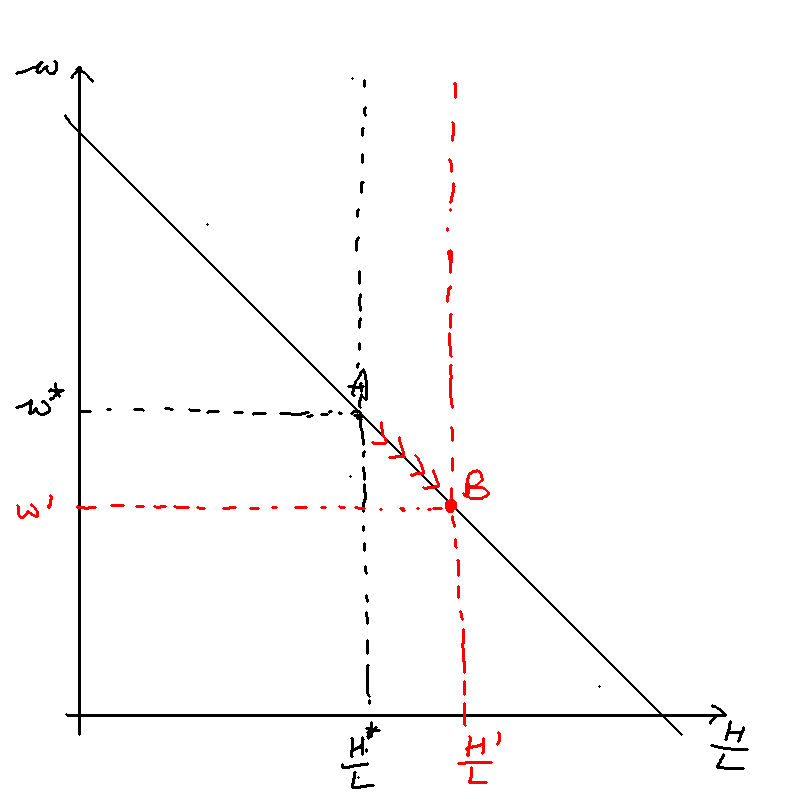

Let's take a look at this last equation, and plot it in a graph with x-axis . We can see that as the number of skilled workers increases (), the lower the wage premium.

An increase in skilled workers () leads to a decrease in wage premium (movement from ).

Review questions

What is the production function stated by Acemoglu?

What is the skill premium?

What is the elasticity of substitution? How does it relate to \(\rho\)?

Solving the paradox by directed technical change

We have just formalised the result that as the relative ratio of high-skilled workers increases, the wage premium decreases. This is great, but how then can we explain the empirical finding that the skill premium has increased over the decades? The answer is a combination of both elasticity of substitution and a skill-biased technical change. Looking once again at the previous equation, we see that can increase if the term

increases.

Under what circumstances will this term increase? Well, one way is to increase . But an increase in will only increase this term if . If workers are not very substitutable (), an improvement in the productivity of skilled workers reduces the skill premium. This case appears paradoxical at first but is in fact quite intuitive. As Acemoglu says:

Consider, for example, a Leontieff (fixed proportions) production function. In this case, when increases and skilled workers become more productive, the demand for unskilled workers, who are necessary to produce more output by working with the more productive skilled workers, increases by more than the demand for skilled workers. In some sense, in this case, the increase in is creating an “excess supply” of skilled workers given the number of unskilled workers. This excess supply increases the unskilled wage relative to the skilled wage.

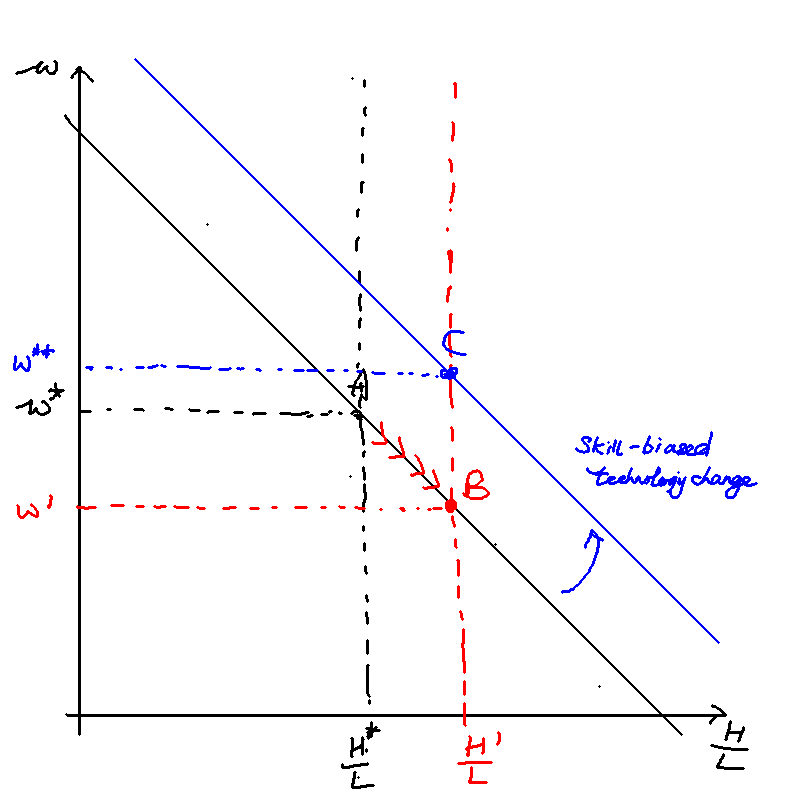

Okay. So suppose . Then, an increase in will indeed increase the wage premium by shifting the line upwards.

Figure 2 illustrates. Despite the increase in H/L, skill-biased technology change causes the wage premium to increase from to .

Great---we have solved the paradox by introducing skill-biased technical change. More explicitly, the relative productivity of skilled workers,

must have increased.

Acemoglu's model with endogenous directed technical change.

I've just shown that one can have an increase in the ratio of high- to low- skilled workers IF the coefficient of substitution AND technical change is directed towards high-skilled workers.

But that begs the questions: why was technical change directed towards high-skilled workers? Now we attempt to endogenise technical change (i.e. try and find a reason within the model why technical change was directed).

We have our utility/production function once again:

Here, let's introduce some innovators. Innovators can produce innovations, or , that increase the productivity of all high- or low-skill workers. Let the fixed cost of producing an innovation be B and let the marginal cost of producing the new technology be 0. Then the marginal benefit of providing a new technology is simply the marginal increase in productivity ( or ) multiplied by the price of that good; this gives and respectively.

We can see that innovators will only choose to produce an innovation if they stand to make a profit: in other words only when .

Here, there are two factors that affect innovation: price and market size.

Price effect: the larger the price of the good , the more profit innovators stand to make.

Market size effect: The more high- or low- skilled workers , the more profit innovators stand to make.

There is a further equilibrium condition. At equilibrium, the marginal benefit of providing both high- and low- skilled technologies must be equal. Otherwise, people would start developing more technologies of the other one to make more profit.

This gives us the following condition:

By consumer optimisation,

After all, consider the case where LHS > RHS. Then, it would be a Pareto improvement to substitute 1 unit of H for 1 unit of L.

But we know here that the production and utility functions are the same! Thus,

and

Therefore, we can reuse the previous result

Substituting in the equilibrium condition, and replacing $$\sigma = 1/(1- \rho)$$ gives us

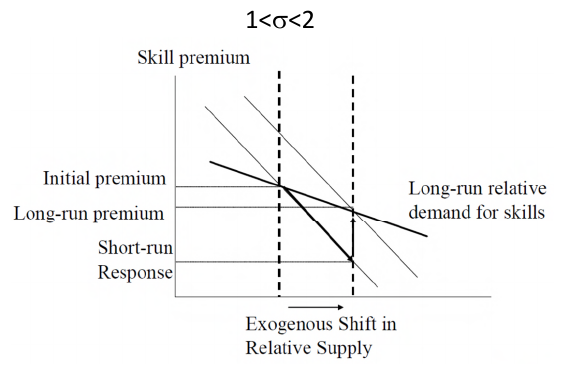

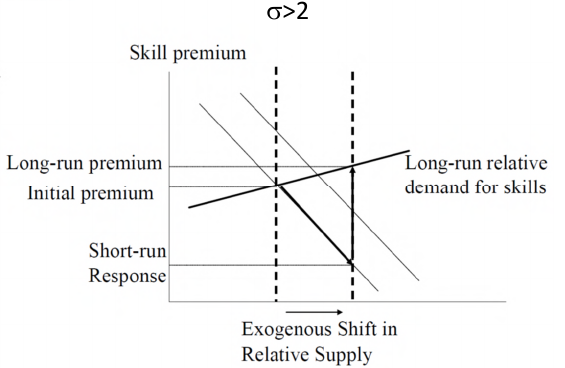

This gives the result that when , more technology will be produced for the higher-skilled worker if H/L increases (i.e. the market size effect dominates). In other words --- directed technical progress! This is something we previously assumed in the exogenous case, but now we have shown how directed technical progress is in fact caused by a large supply of high-skilled workers.

Okay, we've shown that if , when , . But what about the skill premium?

Substituting the result we got for into the equation, as well as the fact that , we obtain

This result tells us that if , then an increase in relative supply of high-skilled workers increases the skill premium. Note that this is different from the exogenous model. In the exogenous model, as long as $$\sigma > 1$$ both the level of skill-biased technology and the skill premium increase. In the endogenous model, if the level of technology does increase, but the skill premium actually decreases (the increase in supply outweighs the increase in technology).

| Level of | Exogenous model | Endogenous model |

|---|---|---|

Comparison to other models

In the Schumpeter-Solow case, demand for innovation is gotten from , level of capital per effective labour unit. The greater is, the more profit innovators stand to make.

TODO

Conclusion

TODO